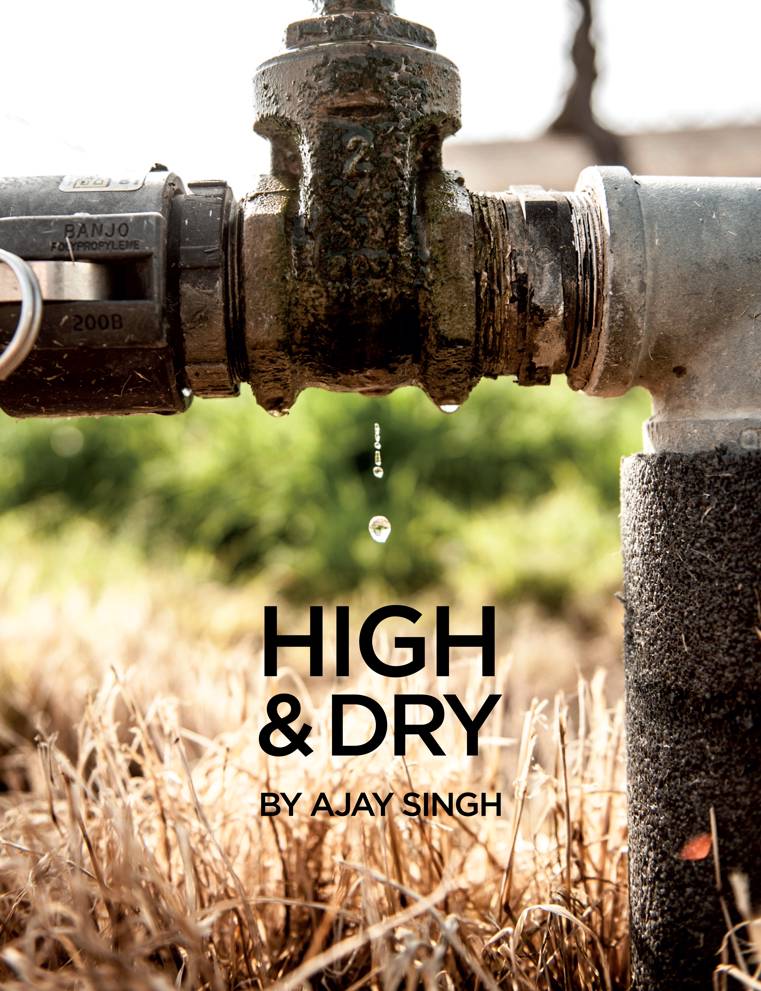

High and Dry

California’s San Joaquin Valley produces 25 percent of America’s food on just one percent of the nation’s farmland. Its economy and its people depend on agriculture. The region is in its fourth straight year of drought, and facing a second year of zero water allocation. In February, California’s water authority denied a plea to send more water to the parched Central Valley, citing the plight of smelt and Chinook salmon inhabiting the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Local farmers, residents, and grassroots activists are aghast, asserting that “water is a civil right, a human right” and that the state should be more concerned about the livelihood and welfare of its people than with the fate of fish.

As a boy growing up on the vast alluvial plains of California’s San Joaquin Valley in the 1960s, Alan Sano spent much of his free time out in the fields of his small family farm. When the tomato harvester broke down, he was always eager to help. “My father would ask for a wrench, but I didn’t know what a wrench was,” recalls Sano. “I’d bring a screwdriver and my dad would yell at me.”

It wasn’t long before Sano mastered the skills he needed to succeed as a farmer in the world’s most productive agricultural region. A third-generation Japanese-American, he dropped out of high school to work with his father, helping expand the family’s agricultural holdings twelvefold—from 328 acres to a little more than 4,000. Despite an auto accident in the 1980s that left him paralyzed from the waist down, Sano, 52, still gets around on the farm: He wheels himself with his bare hands in the dirt, personally supervising the care of crops ranging from tomatoes, cotton and garlic to garbanzo beans, almonds and pistachios.

Over the past few years, however, Sano’s kinship with the land has unraveled. California is entering its fourth straight year of drought in 2015. It’s a prolonged dry spell that many deem historic. As many as 25 counties have declared local emergencies, and the water shortage has made farming in the region increasingly difficult.

Last year was particularly bad. In January 2014, the Bureau of Reclamation, a federal water management agency best known for building dams, power plants and canals across America’s 17 Western states, enforced a zero water allocation law on California’s entire farming community. (On February 27, the bureau decided to allocate zero water for 2015, with the provision that if rainfall and other conditions improve as the year progresses, the restriction might be relaxed.)

It was the first time in 47 years—canal water was introduced to parts of the San Joaquin Valley in 1967—that farmers like Sano had to go without any government-supplied surface irrigation whatsoever. By contrast, federal authorities allocated 50 percent of the usual supply of canal water for municipal and industrial use statewide. Canal water to support wildlife got 70 percent of its typical share.

Like other farmers, Sano compensated for the cutbacks by doing what his father did before spectacular canals transformed irrigation: He pumped groundwater. But after more than a century of exploitation, not to mention contamination, groundwater levels have receded so drastically that Sano was able to irrigate only 65 percent of his crops. What’s more, Sano was dipping into California’s largest source of water storage during drought years. Groundwater is also the only lifeline for many municipal, agricultural and disadvantaged communities, which rely on it for nearly all of their water supply.

The long-term environmental effect of pumping groundwater is a geological phenomenon known as subsidence. First detected in the 1920s, it refers to the gradual settling or sudden sinking of land resulting from the movement of underground materials. Although it has various causes, including subsurface mining, more than 80 percent of the subsidence identified in the U.S. is a consequence of the excessive pumping of aquifers and their collapse, according to a 1999 report by the U.S. Geological Survey. Subsidence has many harmful consequences, including migration of rivers and displacement of wetlands. But its most destructive effect during periods of drought is the permanent loss of storage capacity in aquifers, which further depletes accessible groundwater.

San Joaquin Valley has some of the world’s worst subsidence—and the problem is spreading. “We found it in a new place recently,” says Michelle Sneed, a hydrologist with the USGS. That new place is the town of El Nido, California, where land is sinking as much as a foot every year. “That’ll be 50 feet in 50 years,” says Sneed, summing up the slow-moving geological disaster. “The only place in the world subsiding as fast is Mexico City.”

Partly because agriculture without subsidence depends on an uninterrupted supply of surface water, the federal and state governments designed two mammoth water-delivery schemes known as the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project. Both capture and store water in dammed reservoirs for redistribution through rivers and canals, mostly from northern California, which gets 75-80 percent of the rain in the state. The projects were meant to offer sustenance during periods of prolonged drought, and have enabled the Central Valley, of which the San Joaquin Valley is the southern two-thirds, to produce about 25 percent of table food for Americans on just one percent of the nation’s farmland.

“The early years of subsidence brought about the need for project water to flow south and to eliminate the region’s dependence on groundwater,” says Gayle Holman, public affairs representative of the Westlands Water District, which covers more than 600,000 acres of farmland in western Fresno and Kings counties, making it the nation’s largest local government entity responsible for providing surface water for agriculture.

“But today,” adds Holman, “because of federal regulations that don’t consider impacts on farmers and other people, as well as businesses and those who rely on the agriculture industry, the projects are broken.”

One way of looking at California’s water issues, which reflect those in most states across the American West, is as a giant battle between competing stakeholders. “In this particular drought, you could define waste as ‘somebody else’s doing,’” says Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis, and a professor of civil and environmental engineering. “Everybody’s a villain and everybody’s part of the solution.”

The first step in trying to find a way out of the crisis is to understand just how deep it is. “If you step back and look at the southwestern United States—Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, California—what you would find is that for most of the 21st century, every single year a large portion of the Southwest has been in a drought,” says Glen MacDonald, a UCLA professor of geography and an expert on droughts and water resources. Greenhouse gases exacerbate the water shortage, he explains, raising temperatures and causing water to evaporate at higher rates.

“If you take a look at 2014, you will find that while rainfall has been low, it wasn’t record-breaking,” says MacDonald, adding: “The drought would not have been so serious if it weren’t for those super high temperatures.” By all accounts, California and much of America’s West are in the grip of a megadrought. “Right now we’re getting a preview of what the 21st century will be like and how we can act upon it so that we can start planning for the future,” MacDonald says. “This drought is a great wakeup call.”

Alan Sano’s farm is located in Mendota, a largely agricultural town in the Westlands, roughly halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. To get to it, you drive east from Interstate 5 toward Firebaugh, a city named (but misspelled) after A.D. Fierbaugh, who established a trading post there in 1854. This is a region of America’s Far West where human enterprise has always been as wide as the sun’s arc. But except for the occasional bark from a dog, there are few sounds here—no voices of yeomen in the nearby fields, and except for the sound of wells being repaired, not even the din of iron against iron and iron against earth. It’s as if the driest January on record, capping a full year of zero project water, has sapped farmers’ energies.

Early in 2014, says Sano, he decided to let 1,000 acres of his land sit fallow because of the lack of water. (In a touch of irony, the Colorado River Aqueduct, which transports water 430 miles from northern California to Los Angeles, cuts right through Sano’s land.) But when one of Sano’s six water wells stopped working in the summer, he was forced to fallow another 225 acres. “I just didn’t plant the tomatoes and garbanzos,” he explains, adding that the total loss in seeds and greenhouse tomato saplings amounted to more than $100,000. Sano’s employees were also hit. About a third of the 25 or so tractor drivers and irrigators that he typically employs got pink slips.

According to an analysis co-authored by UC Davis professor Lund, as many as 410,000 acres, representing six percent of irrigated cropland in the Central Valley, were fallowed in 2014. The valley is estimated to have lost 14,500 seasonal and full-time jobs—about 6,400 of them directly related to crop production. The total estimated cost—no less than $1.7 billion, including some $450 million in additional costs of groundwater pumping.

The human impact of California’s drought was on stark display during a recent public workshop in Sacramento called by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), which sets statewide water policies. On February 18, a motley group of farmers, seasonal workers, state senators, city managers, fishermen and environmentalists crowded into the California Environmental Protection Agency headquarters to debate a February 3 decision whereby the SWRCB denied a request by the Department of Water Resources and the Bureau of Reclamation to release additional water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta into the reservoirs of much of the drought-parched state.

The extra water would have afforded some room to lift the zero water allocation order affecting farmers. A bipartisan group of legislative and congressional leaders, including U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, opposed the water board’s decision, pointing out that additional pumping had been approved by five state and federal water and wildlife agencies.

What appeared to be a typical battle between various government agencies and the competing interests of California’s water empire quickly distilled to a striking, binary issue. As Courthouse News Service, which caters mostly to lawyers and the media, put it: “Water For California’s Farms—or For Fish?”

Neither fish nor crops can live without water. But does this really boil down to a conflict between farmers and fish? The answer appears to be yes—and SWRCB Executive Director Tom Howard came down on the side of fish. As the official who had initially rejected the federal and state request to export water from the delta, Howard advised the board to heed his decision to shut the delta’s south-facing gates.

“Many fish species are already at historic low levels,” Howard told the board, adding that the 95 percent mortality rate of winter-run chinook salmon, combined with the dwindling numbers of delta smelt, were key factors in his decision not to send any additional water into Central Valley reservoirs.

But the farmers, many of them wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Let Water Flow to People, Not Fish,” aren’t about to give up. Accompanied by local politicians and grassroots activists on the south side of the delta gates, they offered testimony after testimony about the drought’s adverse impact on human lives.

“I’m sorry if I’m offending any business people, but I believe farmers are more important than fish,” said Alvaro Preciado, a resident of the almost exclusively agriculture-based city of Avenal in the Westlands Water District. “Our community is based on property taxes, but people have been moving out or renting, and we’ve been struggling for the last 10 years to provide water to our community.”

Several women, speaking in Spanish translated by interpreters, bemoaned the underemployment in their communities and the difficulty of feeding and taking care of children. “Because of the lack of work in California, I have to go to work in Arizona,” said one speaker, indicating that she spoke for many families like hers. “The heat is immense in Arizona and the children are forced to leave school to help.”

An even sharper look at the south-of-delta misery index came from Andy Souza, president and CEO of the Fresno-based Community Food Bank, who said that his organization feeds 6,000 to 10,000 people monthly. “We’re serving families that would have never stood in a food line,” he said. Since May 2014, he added, he has observed “a sense of helplessness and hopelessness in the families we serve.”

The most blunt criticism came from Maria Gutierrez, a volunteer with El Agua es Asunto Todos, a Fresno-based nonprofit Latino community alliance whose name translates into English as “Water is Everyone’s Business.” The SWRCB’s decision not to add water to Central Valley reservoirs is “a slap in the face of Latinos living south of the Delta,” she said. “People are very angry—we believe water is a civil right, a human right.”

These sentiments echo plenty among people on the drive east from Alan Sano’s farm to the town of Mendota, which used to be known as the cantaloupe capital of the world. Along the way, it’s easy to see how the crop patterns have changed—away from so-called row vegetables such as tomatoes to high-value “permanent crops” such as almonds and pistachios. Permanent crops have been criticized for taking years to mature and for being highly water-intensive. For example, farmers must wait four years to get their first crop from an almond orchard (pistachios take seven years), and almond trees require three to four feet of standing water per acre—enough to supply the annual water needs of six to eight California households.

Besides the fact that permanent crops are financially lucrative and help offset the relatively slim profit margins on row crops such as tomatoes, farmers favor them for one other key reason that, paradoxically, revolves around the water cutbacks. “If you don’t have regularly allotted water and you have to buy it from outside sources at exorbitant prices,” explains Holman, “you have to grow high-value crops—and right now the highest-value crop is almonds.”

Regardless of the economics—and arguably the ethics—of planting orchards where vegetables used to grow, it’s clear that there aren’t enough fields being planted to keep people working.

“If I worked every day in the fields for eight hours a day, I would make about $700 a week,” says Joel Gonzalez, a 33-year-old local resident who came to Mendota from Mexico City when he was 3 years old. He has been out of work for a few months and says he makes ends meet by doing odd jobs such as tile work and carpentry. “Some people go two hours away to find work, in Paramount, Los Banos, Merced—wherever contractors take them,” he says. “They even go to Santa Rosa, up north.”

Like Gonzalez, tractor driver Magdaleno Martinez hasn’t had a fulltime job for months—since October 2014, to be precise, when the last crop of melons was picked. Asked how he survives, Martinez, 50, replies that he gets enough from unemployment to rent a $250 one-room apartment, where he cooks his food on a hotplate.

About an hour’s drive from Mendota lies Los Banos, a relatively prosperous city with a name meaning “the baths” in Spanish, a term used in the mid-19th century to refer to pools near the source of a local creek. Los Banos is outside the Westlands, in Merced County, and much of the land here is markedly wetter. This is also where, cutting through broad expanses of farmland on both sides, lies a street named Henry Miller.

You would be forgiven for thinking that someone with a decidedly literary mind must have lobbied for that name. In fact the street has nothing to do with the Henry Miller who penned Tropic of Cancer, but the man for whom the street is actually named is the subject of a noteworthy book—a 2001 title by David Igler, a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine.

Industrial Cowboys tells the story of two San Francisco butchers named Henry Miller and Charles Lux. The duo found land in Los Banos and by “monopolizing land, water and other resources provided an insurance policy against the West’s drought and flood cycles and its complex natural environment … ultimately fostering enduring contradictions between the Far West’s natural and social landscapes.”

As it turns out, Henry Miller (the rancher) created “one of the first vertically integrated farming operations in California, from manufacturer to seller, up the whole supply chain,” in the words of his great-great-great-grandson, Cannon Michael. An heir to a large chunk of the Miller-Lux ranch empire, Michael is president of the Bowles Farming Company, Inc.

Bowles Farming owns 4,000 acres in Los Banos and leases 7,000 more from other family members. Like a lot of other farms in the San Joaquin Valley, this is a big operation that produces everything from fresh-market tomatoes, onions and carrots, to alfalfa and high-quality cotton. What distinguishes Michael as a farmer, however, is that he maintains a habitat on his land for migrating ducks from Canada. What’s more, his estate sits next to the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge, home to one of the last populations of the Tule elk, a subspecies found only in California.

And yet, for all his resources and obvious connections, Michael has been impacted by the drought. “I don’t purport to have the saddest story,” he admits, “but about 800 acres on my ranch is fallow now because of the water crisis.” Michael generally employs about 60 workers on a seasonal basis, but he says he had to cut his labor force by 15 percent last year. And for the first time ever, Michael asserted his historic water rights from the San Joaquin River, thereby depriving other farmers of precious irrigation.

A former commercial real estate agent who majored in English and minored in economics at UC Berkeley, Michael is a far cry from the typical farmer in the San Joaquin Valley. Which just goes to highlight the struggle of the common farmer trying to survive in these hard times.

“That’s the thing about farming—it’s a very capital-intensive business, and every year is critical to us,” Michael says. “You can’t start and stop—you have to keep going.”